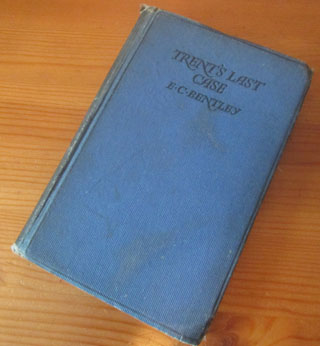

Trent’s Last Case

Trent’s Last Case

E. C. Bentley

First published in the UK 1913 by Nelson

This edition possibly 1928*

325 pages

Source: My own collection

G. K. Chesterton called Trent’s Last Case ‘the finest detective story of modem times’. Short story maestro Edward D. Hoch called it ‘One of the true cornerstones in the development of the modern detective novel’. The critic Ian Ousby wrote that ‘Bentley… also had Chesterton’s confidence that detective fiction could carry provocative ideas.’ It is number 34 in the CWA’s top 100 crime novels and in that list H. R. F. Keating says, ‘it gave our art a new direction’.

The author, humorist Edmund Clerihew Bentley, is also known as the inventor of the clerihew, a 4-line biographical poem, for example:

Sir Humphrey Davy

Abominated gravy.

He lived in the odium

Of having discovered sodium.

He was a school friend of G. K. Chesterton, who encouraged him to write the book, possibly to stop him writing clerihews. Once published, he left it 20 years before publishing the follow-up Trent’s Own Case and a handful of short stories.

Trent’s Last Case opens with the death of Sigsbee Manderson, an American plutocrat with a talent for gathering fortunes. Bentley clearly has a dim view of this sort of chap:

When the scheming, indomitable brain of Sigsbee Manderson was scattered by a shot from an unknown hand, that world lost nothing worth a single tear;

And when the death causes a few days of chaos, suicides and ruination on the stock market:

All this sprang out of nothing.

Nothing in the texture of the general life had changed. The corn had not ceased to ripen in the sun. The rivers bore their barges and gave power to a myriad engines. The flocks fattened on the pastures, the herds were unnumbered. Men laboured everywhere in the various servitudes to which they were born, and chafed not more than usual in their bonds.

Philip Trent is a gentleman-artist who has made himself a name as a sleuth, using his eye for detail and intuition to crack unsolvable crimes. He came to prominence solving a murder just through reading newspaper accounts of the crime (like Poe’s Dupin in ‘The Mystery of Marie Rogêt’). He is called in to the Manderson murder by newspaper magnate Sir James Molloy, who has employed him as a journalist-detective for the Record in previous cases. He is described as:

a long, loosely built man […] His high-boned, quixotic face wore a pleasant smile; his rough tweed clothes, his hair and short moustache were tolerably untidy.

He shares Bentley’s views:

‘I tell you frankly, I wouldn’t have a hand in hanging a poor devil who had let daylight into a man like Sig Manderson as a measure of social protest.’

But despite this Trent quickly sets to work analysing the evidence, set up in friendly competition against his old adversary Inspector Murch of Scotland Yard. He soon has everything wrapped up – based on a close inspection of a pair of Manderson’s dress shoes – and leaves.

And that’s all I can tell you about the plot.

Bentley intended his book to be a send-up of the mystery genre, but in fact it has been more influential than subversive. You can see the roots of a good many tropes in Trent’s Last Case. Trent’s sense of humour and talent for bathos comes through in his descendants Campion and Wimsey amongst others.

‘I should prefer to put it that I have come down in the character of avenger of blood, to hunt down the guilty, and vindicate the honour of society. That is my line of business. Families waited on at their private residences.

Definite shades of Campion’s guise as universal uncle and the man come about the trouble. And here is Wimseyesque facetiousness:

‘Why sit’st thou by that ruined breakfast? Dost thou its former pride recall, or ponder how it passed away?’

Another one is his friendly rivalry with Inspector Murch of Scotland Yard, based on the ‘principles of what he called detective sportsmanship’, i.e. the open withholding of evidence from the police.

‘I am going to cut you out again, inspector. I owe you one for beating me over the Abinger case, you old fox.’

And finally, there is falling in love with a suspect. I can see this happening, of course, but in Trent’s Last Case it happens at first sight, which doesn’t seem especially realistic for someone of the detective’s age and background. Still, in falling in love, Trent gave the mystery story a new twist.

Oddly, this was the third time I started Trent’s Last Case, but the first time I finished it. Not sure why, as it is a good mystery written with a light touch. So, if you’re enjoying the British Library’s golden age reprints, this might be one to pick up next.

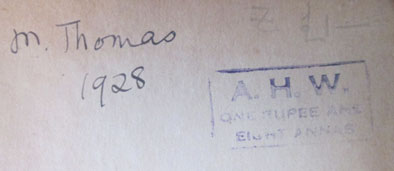

* No idea what year my edition was printed, but it is inscribed M Thomas 1928 and cost one rupee and eight annas. A. H. W. refers to A. H. Wheeler, an Indian bookshop chain which operates from railway stations, so their equivalent of W. H. Smith.

See also:

*SPOILERS*

Scott Adlerberg at Criminalelement: “I am afraid I startled you,” Trent hears the real murderer say, and one can imagine how readers of the time were startled. Trent the man of perpetually high spirits breathes out “in a laugh wholly without merriment.” Not that contemporary readers will react with amazement; we’re accustomed to stories with fallible detectives and endings that reveal a bitter truth. For that matter, the tradition goes back to perhaps the very first “detective” story, Oedipus Rex. But in the realm of popular mystery fiction, Bentley without question did something innovative and unusual for his time, and what’s also true is that as a mystery genre reader I needed time and mystery reading experience to “get” it.

A Penguin a Week: I expect that most of the plaudits for this book reflect its influence, as the remote setting, the unpopular victim, and the gentleman sleuth are all integral elements of detective fiction in the following years. I enjoyed it more for this story of the gradual maturing of Trent. And because of the complex and shifting nature of the solution, although his cannot be explained further without giving the whole thing away.

The Rap Sheet: Yes, Trent is fallible. And yes, his weakness in falling in love with a prime suspect is a device that is later borrowed with great success by future crime novelists and filmmakers.

I have read this one but it failed to register in my memory at all. Maybe I’ll take another one day

LikeLike

Though the first half is a bit slow, it is a good mystery with an ingenious plot and a surprising and satisfying final twist.

You seem to have an interesting copy, originally bought by one M.Thomas in 1928 from an Indian railway station bookstall !

Though A H Wheeler was founded by a Frenchman, it is presently fully owned by Indians (Banerjees). Its interesting history is available at http://ahwheeler.com/?page_id=37

LikeLike

Read this many years ago and still recommend it to people!

LikeLike

The most I remember about reading this (many, many moons ago) is that I thoroughly enjoyed it. It’s on the TBR stack to reread at some point. This very edition, in fact, less the inscription–thanks for giving me a target pub date,

LikeLike

I take that back (after checking)…mine is more aqua-blue. Darn…that keeps the pub date of mine a mystery.

LikeLike

Pingback: Book of the month: March 2015 | Past Offences Classic Crime Fiction