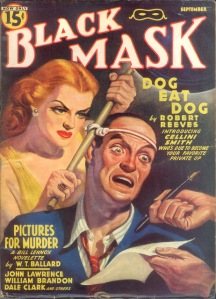

‘Okay, maybe I’m sadistic, but this one just speaks to me,’ says Evan Lewis of his favourite Black Mask cover, at Davy Crockett’s Almanack.

October was less crowded with classic crime activity than September, but still presented me with some great reviews and articles to collect together here (and to think when I started this blog I thought classic crime was a neglected area…).

I love a good crime reference, so I was interested to read J. Kingston Pierce at The Rap Sheet give an insider’s view of the making of 100 American Crime Writers:

One of the first tasks was to revise the list of authors to be included. Deciding which names would stay in 100 American and who to take off was always going to be a difficult task. There are some authors which no anthology of this kind can do without: Raymond Chandler, Dashiell Hammett, Elmore Leonard, etc. But I decided to add some relatively new names in the field, such as Megan Abbott, and take off John Grisham and Scott Turow, who–good as they are–just did not fit as neatly into any crime genre. However, some authors such as William Faulkner and Truman Capote, who would not traditionally be considered crime writers, are included for their influence on the genre…

Another crime reference got an airing when The Passing Tramp presented a detailed and respectful obituary of the critic Jacques Barzun:

Much to my regret I never met or corresponded with Professor Barzun, but as a reader of mystery fiction (and more recently a historian of it) I have lived with Barzun’s powerful presence in my mental life for over two decades, ever since I read his and his colleague Professor Wendell Hertig Taylor’s magisterial critique of crime fiction, A Catalogue of Crime.

Returning to fiction, Malcolm Forbes at The Daily Beast took a look at the Pepe Carvalho novels of Manuel Vázquez Montalbán (namesake of everybody’s favourite Sicilian policeman Montalbano, apparently).

When not solving fiendish mysteries, Carvalho the bachelor gourmand is both cooking and appreciating fine food, indulging in amorous interludes, engaging in political debate, and, oddest of all, burning philosophical books. Accounts of these eccentricities often make for more interesting reading than the cases he is investigating, but both have contributed to the books’ widespread European popularity. The English-speaking world appears to be playing catch-up, a matter that will be rectified with Melville House’s reissue of five of the best adventures.

I have only read one Carvalho, the 1992-set An Olympic Death, and whilst I enjoyed the story I did find his habits and domestic set-up inexplicable.

Over at Tipping My Fedora, a discussion of one of my favourite Campion novels, Traitor’s Purse, turned into a discussion of my favourite Campion novel, The Tiger in the Smoke, and the movie version thereof (which I saw by chance, about 20 years ago, and have never seen again).

It also led me to an A. S. Byatt article in the Telegraph – Why I Love Margery Allingham – in which she provides a lovely potted overview of Campion’s career (by the way Amanda is Campion’s future wife, and Lugg his faithful manservant):

Traitor’s Purse has the best single idea I’ve met in detective fiction. During the phony war, Campion is knocked on the head and wakes with almost complete amnesia in a hospital. He spends the whole, taut novel not knowing who he is – nor who Amanda is, nor who Lugg is.

It becomes clear that he alone is in possession of a dreadful secret that threatens his country. He has to foil a plot at the same time that he has to discover who he is.

Because he is vacant he forgets to look vacant – “almost intelligent”, Amanda says he looks. Because he forgets to act a part he becomes a man of action. Because he forgets Amanda he realises he loves her. And of course he foils the plot. If I had to vote for the single best detective story, this would be it.

Sticking with Campion, Dana Stabenow delivers a lovely short review of The Tiger in the Smoke.

But what I love most about this book is the character descriptions. Take Campion’s associate, Divisional Detective Chief Inspector Charles Luke:

Charlie Luke in his spiv civilians looked at best like a heavyweight champion in training… His pile-driver personality… It made him an alarming enemy for someone.

When he is detailing a subordinate to accompany an unwilling Canon Avril, Luke says, “He’s my senior assistant, a quiet, discreet sort of man,” he added firmly, eying the sergeant with open menace.” You’d develop quiet discretion, too, if Luke looked at you that way.

Over at Shadepoint a new series of reviews of the Inspector Morse canon begins with Last Bus to Woodstock.

Hard to imagine this novel being the starting point for the phenomena to come (Morse, Lewis and now, Endeavour) with its slightly ragged ending, and feet firmly in an older decade, but that’s exactly what it is. I believe it is the strength of the characterisation, even at this early stage, the interplay between Morse and Lewis, and Morse’s almost beaten, hunted sort of persona, that is the key.

An Australian classic I still haven’t got around to reading is Arthur Upfield’s The Battling Prophet (1956), reviewed at Mysteries and More. Upfield created an Aboriginal detective with the memorable name of Napoleon Bonaparte:

“I was found beneath a sandalwood tree, found in the arms of my mother, who had been clubbed to death for breaking a law. Subsequently, the matron of the Mission Station to which I was taken and reared found me eating the pages of Abbotts’s Life of Napoleon Bonaparte. The matron possessed a peculiar sense of humour. The result – my name. Despite the humour, she was a great woman. Aware of the burden of birth I would always have to carry, she built for me the foundations of my career. My entry to the Queensland Police Department came about after I had won my M.A. at the Brisbane University, …..”

The Puzzle Doctor had a busy month, beginning with a review of Ellery Queen’s The Four of Hearts, and also taking in Carter Dickson’s Seeing is Believing.

A simple experiment in hypnotism to prove that you cannot make someone act against their nature. A woman is hypnotised and given a gun that she believes is real and asked to kill her husband. As expected, Vicky Fane cannot pull the trigger. She is then given a knife that she knows is made of rubber and, knowing that it is harmless, plunges it into his chest… except the knife, that no-one had been anywhere near during the experiment, has miraculously turned into the genuine article, and Arthur Fane is lying dead on the floor…

Finally, Craig at CrimeSquad reviewed Bello Books’ new electronic edition of the Francis Durbridge suspense novel My Wife Melissa.

‘My Wife Melissa’ is a riveting read and one that will keep you entranced for a quiet afternoon. Durbridge was a master storyteller and his enthusiasm for a ripping good yarn shines through in this enthralling tale.

I’ve got hold of another Bello reissue, Roy Vickers’ The Department of Dead Ends, which I will be reviewing soon.

Rich – A terrific summing-up, for which thanks! I never do get to nearly as many blogs as I’d like, so I appreciate your putting this together. 🙂

LikeLike

Thanks Margot – glad it’s useful. I miss loads out, of course.

LikeLike

Thanks Rich. As usual a great round-up and now I just need to find time to visit all the sites to read the reviews.

LikeLike